By Nurture Connection

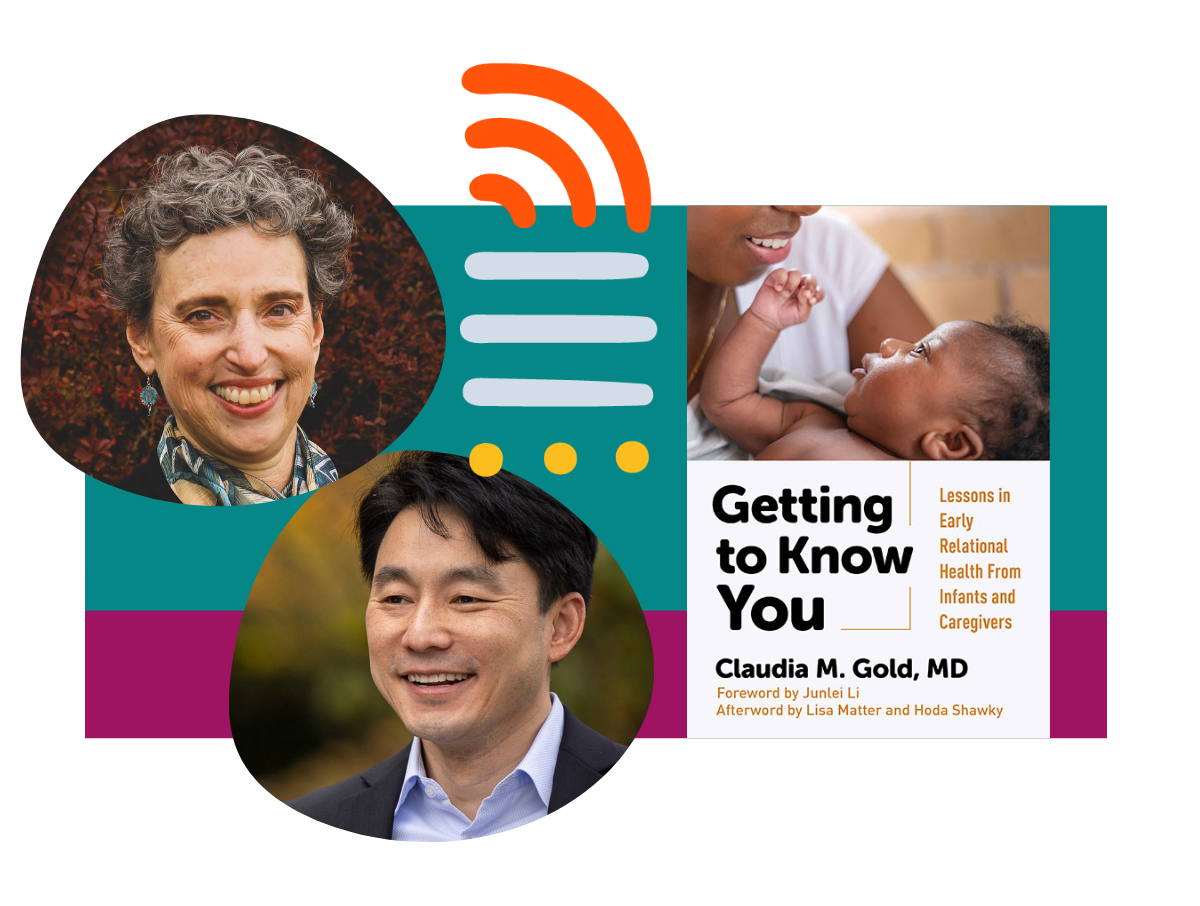

Claudia M. Gold, MD, is a pediatrician and writer who practiced general pediatrics for over 20 years and now specializes in Early Relational Health (ERH). She has clinical experience in a broad variety of communities and speaks frequently to both lay and professional audiences. In her latest book, Getting to Know You: Lessons in Early Relational Health From Infants and Caregivers (March 2025), Dr. Gold encourages readers to “listen in” and embrace differences as a relational model for building deeper connection, growth, and healing. One of her previous books, The Power of Discord: Why the Ups and Downs of Relationships Are the Secret to Building Intimacy, Resilience, and Trust, explores how working through the inevitable dissonance of human connection is the path to better relationships.

Junlei Li, PhD, Saul Zaentz Senior Lecturer in Early Childhood Education and Co-Chair of the Human Development and Education Program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education as well as a Nurture Connection Steering Committee member, spoke with Dr. Gold about principles of ERH; the essentiality of centering connection, growth, and healing in relationships; and how discord can be a pathway for relational repair, growth, and healing — both within ERH and this present moment. Dr. Li wrote the foreword to Getting to Know You.

“Caregivers really want someone to listen to their experience and to feel heard — in the same way their child wants to feel heard.”

–Claudia M. Gold, MD

Junlei Li: Claudia, it is such a wonderful treat to be in conversation with you. After reading two of your books, The Power of Discord and then the latest one about Early Relational Health (ERH), Getting to Know You, I was reflecting on how over the last hundred years or more, talking about and trying to understand relationships has been this strong and constant theme in human development research as well as in practice. Yet once again we’re talking about relationships — so obviously there is so much more that we still need to understand.

What drives you to keep wanting to understand and talk about relationships, and what do you think this can do for the broader work of caring for children and families?

Claudia Gold: That’s such a great question and something we often talk about in the field of pediatrics. Since the 1980s, when we first started talking about relationships in the context of addressing new morbidities, and now, over 40 years later, we’re still talking about relationships. And the best answer I can give is because we need to be advocates for children and their caregivers. Now, on the question of why it is so hard to get this message across, I don’t have the answer for that. Perhaps it might be that relationships are really hard to think about because — as somebody once described them to me — they are evocative.

In this book and in my work, my hope is to get really granular and try to understand what is actually going on in relationships. I aim to tackle this issue of shame and blame and all of the difficult or uncomfortable things that come with relationships head-on. Simultaneously, I want to keep with my “not-knowing” stance when I’m with children and families. What also drives me is being with families where the status quo may be “what is wrong with my child?” and the expectation is for me (as a pediatrician) to give a diagnosis or a behavior management solution.

However, when you enter into this work centering relationships, you uncover things that give meaning to the child’s behavior and can also be transformative for the caregivers. So it’s not only giving voice to the child but also to the caregivers. They really want someone to listen to their experience and to feel heard — in the same way their child wants to feel heard.

Embracing “Not Knowing”

Junlei: You just mentioned something that I found striking in your new book: this idea of a not-knowing stance. What it reminded me of is how much (at least within the last few decades) of early childhood work does not exhibit that stance. In fact, it seems to exhibit a “we’re the experts” or an “all-knowing” stance. I just think back to things in the early childhood field that have driven the narrative, the rhetoric, even the policies of early childhood. All of which makes the perspective in your book completely refreshing. What do you think is the biggest difference that happens — for both parents and clinicians — when we move from an all-knowing stance to actually listening to people?

Claudia: All of us want to be seen and heard, and this also counts for everybody we interact with in our professional lives. As pediatricians, we are very guilty of defaulting to dispensing information. For instance, we may be instructing parents about ways to play with their children, but we need to remember that parents are the experts with their child.

If they’re not playing with their child, there are likely reasons that’s making it hard for them, and we need to get to that piece. If we simply default to giving instruction and information, we won’t know where the person is coming from, what’s going on with them. And that, at best, is not helpful and, at worst, alienating.

Junlei: I feel similarly. To truly embrace ERH, it pushes all of us to have to change our stance. What I’ve experienced in ERH work is that rather than being purely scientific or even perhaps technocratic work, it is grounded in themes of equity and inclusiveness, of understanding and appreciating caregiving practices across different settings and cultures. But you also brought up this fascinating challenge in your book around the concept of “cultural competence” and how it is fundamentally flawed. And you advocated for an alternative, which is “cultural humility.” Why is cultural competence a flawed concept?

Moving With Relational Humility

Claudia: Well, two things. Firstly, all of the ideas in my book are rooted in our prototype relationship, which is the newborn with their parent or caregiver where there are these two different people (in mind and body) and they need to get to know each other. That is a microscopic developmental process.

Secondly, I see this process as being similar to the process of getting to know any person who’s different from us. The downside of cultural competence is it assumes that there is a category of identity, and that all the people within that category are the same. On the other hand, cultural humility embraces the differences within the sameness.

Junlei: You write at length about trauma in the book as well. And I wondered if our current language or the way we talk about trauma may fall into the same kind of trap as cultural competence does.

Claudia: Yes, exactly. I think it’s an oversimplification and perhaps even a way to separate ourselves by creating this sense of othering . . . a kind of “not me” phenomenon. And it has a way of pathologizing human experience.

Everyone has experienced some degree of trauma. A colleague of mine used to say, “Intergenerational transmission of trauma is what we used to call life.” That’s why in my work when it comes to trauma, I try to use it as a way to recognize that something happened over time — as opposed to pathologizing the human experience, which doesn’t capture the complexity.

In the book, I used the terms “adversity,” “trauma,” and “loss.” I find that “loss” as a term captures the experience in a way that tells you how you can change, because then you can think about processing loss, and grieving and mourning become ways to move past it.

Meeting in the Moment

Junlei: So what term would you use instead of “trauma-informed care” that captures this way of contextualizing trauma?

Claudia: I’m going to borrow from Shawn Ginwright (whose work I referenced in the book), and he uses the term “healing-centered engagement” because what we’re really talking about is engagement between people. What we call trauma-informed care is really facilitating moments of meeting; those moments where you change in relation to another human being, where you change your sense of yourself in the world.

Junlei: Bringing this idea of creating moments of meeting to working with children . . . Young children are not naturally expressive verbally, especially if they’re distressed and upset. Yet I’ve seen so many instances in which care providers intuitively know what’s going on with these children. That a “place of meeting” often comes in very nonverbal forms.

Claudia: Exactly. One thing I talk about in the book is the power of infant observation; babies are so amazing at how much they can tell you about themselves.

I was working with a family that had a one-year-old who wasn’t talking. The parents were so very much burdened by the pressure of everybody telling them that by age one, their child should be talking, which of course is not true. But anyway, they were very vulnerable. When the child would point to something, they would say that thing to try to get him to use the word, and the boy would throw himself on the floor.

And I said, “Well, great, you know he doesn’t really want to be talking yet. He’s just not ready. And he is telling you, ‘No, don’t make me say it.’ This boy is so good at letting you know where he is! You just need to be able to pay attention to that and listen to your child, and not to all these other people who are telling you what to do or what it should be.”

“[ERH work] is grounded in themes of equity and inclusiveness, of understanding and appreciating caregiving practices across different settings and cultures. To truly embrace ERH, it pushes all of us to have to change our stance.”

–Junlei Li, PhD

Closing Reflections

Junlei: I have one last question for you, which is something that I don’t even know how to ask — truly the not-knowing part. In thinking about Early Relational Health and how the American Academy of Pediatrics defined it as: children grow best in safe and nurturing families who are in safe and nurturing and stable communities with a wide range of access to services and resources.

Contrasting this vision as the ideal [for how we support our children and families] with where we are now . . . as we look around, minute by minute, the services and resources surrounding communities and families are becoming more and more scarce, unstable, and unpredictable. And so how do we advance any idea about ERH in a world that is not actively expanding the supports [that families need] but actively dismantling the supports? What do we do as professionals, and what is our message as advocates as well as encouragers of professionals who are out there in this kind of larger context?

Claudia: Well, we’re living in this state of being flooded with fear and terror, and it’s very hard to exist [in that state]. So I certainly don’t know the answer. But I’ll share a story I heard from a family, a couple who have a lot of vulnerabilities specifically to this administration as people who are being targeted and they have a young child. And so they’re living in, not just the kind of fear that we all are living in, but at an exponential level. But they believe their child is what is saving them, because their child calls on them to be present here, now in the moment.

That feels like kind of a metaphor. What protects us from being completely paralyzed with fear is to be in relationship with each other in that very immediate way; to be in community and to be in connection in the way that babies call on us to be. That is the kind of thing that we need in order to have the strength to do whatever we’re going to need to — I hope — get through this unbelievable discord to some kind of repair on the other side. And the only way to keep that hope is to protect ourselves through these moments of really meeting with each other.

Junlei: I’m just processing and listening to how you use the words repair and discord in this context. I’m thinking about how we can — even in children’s development — not be afraid of discord, if we have the conditions and support for repair, and that the repair is really the engine that drives healthy development and resilience. And that in moments like this, we need not be afraid of this externally manufactured discord, but somehow trust that we have the resources, the conditions, and the will to protect and repair not only as individuals but as communities, even as a country and the world.

Thank you, Claudia, I am just so glad to have had a chance to talk with you today.

At its heart, Nurture Connection is an engaged, insightful community of parents, caregivers, researchers, medical professionals, philanthropists, early childhood systems leaders, and policymakers dedicated to ensuring every child has strong, nurturing relationships during their earliest, formative years.

Our “Reflecting Forward” series features guest articles and reflections by dedicated members of our national network, from across the country — who are advancing the Early Relational Health field through practice, research, and parent leadership. These reflections pave paths forward for transforming early childhood systems and imagining new possibilities for children, families, and communities.